Val Workman

The opinions expressed by the bloggers below and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Ryma Technology Solutions. As they say, you can't innovate without breaking a few eggs...

- Font size: Larger Smaller

- Hits: 34628

- 2 Comments

- Subscribe to this entry

- Bookmark

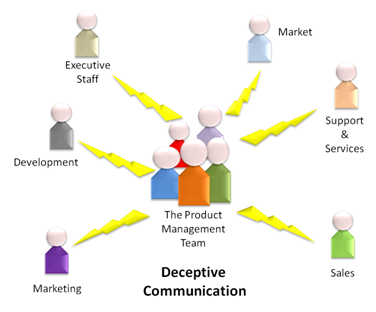

Deceptive Communication

Communication is one of the primary activities of the Product Management team, yet very little is said about communication best-practices. No, I'm not trying to say that the Product Management team should become experts at producing or performing deceptive communication. We study deceptive communication to learn how to avoid producing it inadvertently.

When confronted with deceptive communication, most people aren't even aware of the deception. In these cases apologies sometimes work, but for the Product Management team, sending a deceptive message can be very costly.

Deceptive Communication in Political Affairs

We don't normally think of the Product Management team as being involved in political affairs. The term 'political' is about how decisions are made for a group, in this case the Product Management team. It consists of social relations involving authority or power, and refers to the regulation of product characteristics within an organization and to the methods and tactics used to formulate and apply product decisions.

One sanctioned deceptive message is perhaps best thought of as a political "white lie". When members of the Product Management team, are replaced (it doesn't matter why) we typically don't greet their leaving with sighs of relief, even if that's how we feel. Same thing happens when a product feature that we weren't keen on doesn't make it to a release. White lies are accepted as a way of life between most Product Management team members.

We should take this a little further and consider the relationships the Product Management team has with other internal organizations. I've heard many a product manager, say something like, "Feature X will be out in the next release, but we don't tell Sales yet because they'll start selling it now." White lies are part of the Product Management environment and we need to recognize their impact.

Another sanctioned political deception springs from the largely unchallenged concept of sovereignty. In the past, we thought that it’s justifiable for companies to practice deceit between partners, other business units, and even investors, if it is in their self-interest to do so. It’s only just recently that this thinking has been challenged, and transparency has begun to be considered, at least when we have to. Two issues must be examined when considering this type of deception:

- Do instances of deceptive communication further the enterprise's self-interest or do they deal a blow to it by undermining corporate credibility?

- Even if lying can be demonstrated to enhance certain areas of self-interest, should it be accepted (a means-to-an-end issue, which suggests that lying is an inappropriate communication strategy even if it sometime furthers our competitive advantage)?

Finally, there is an area of political communication that has traditionally cried out with the presumption of truth. An example of this is when a official spokesperson for an organization states the intentions of the product, or describes the product strategy to clients, analysts, and/or partners with the intent of marshaling their support. Once, people required these types of messages to be timelessly cast into stone. If something changed even a year later, the organization or individual would be attacked as being deceptive.

Today, even the most skeptical observers grant a meaningful distinction between opportunistic deceit and clinging stubbornly to past policies clearly out of touch with present realities. Team members accept a shift from a norm of honesty to a norm of deceit or inaccuracy when discussing time sensitive positions. Again, we need to recognize the impact of this type of deceptive communication has on the performance of our products.

Deceptive Communication in Daily Trade and Commerce

The Product Management team can be sucked into all kinds of traps here. Perhaps a whitepaper or book would better serve us, but for now I'm just going to list types. Much of this material comes from "The Federal Trade Commission's Identification of Implications as Constituting Deceptive Advertising." (I.L. PRESTON, 1989).

1. The Proof Implication

- A test of the product is explicitly claimed to exist, and it is implied the test amounts to proof of the accompanying claim.

- Explicit references are made to surveys, and it is implied the results constitute proof.

- Indirect references made to tests imply the existence of such tests, which in turn implies that they prove the accompanying claim.

- Explicit product claims are made that imply the existence of the type of evidence or basis appropriate proof.

2. The Demonstration Implication

- A type of proof implication where the implication occurs by explicate content consisting of demonstration of product performance, rather than be reference to tests or surveys. (Note: Explicitly false demonstrations, e.g. claiming to demonstrate a shaving cream will shave sandpaper when what is actually loose grains of sand sprinkled on Plexiglas - are not included in this type of implication, although of course they are deceptive and illegal.)

3. The Reasonable Basis Implication

- Affirmation representations of a product's future performance, benefits, safety, etc., implicitly represent that there is a reasonable and substantial foundation in fact for making the claim.

4. The No Qualification Implication

- Product claims are broadly stated with no qualification, not even an inconspicuous one. (Note: A major difference between this implication and a proof implication is that for the latter, the proof typically does not exist, while for the former, the claim may be true provided an appropriate qualification is appended.)

5. The Ineffective Qualification Implication

- Product message content contains a qualification, but it is so inconspicuously and/or ineffectively integrated into the message that it is likely to be unnoticed by consumers. The conveyed claim does not include the qualifications.

6. The Uniqueness Implication

- Claims of certain product features are accompanied by the implications that only this product has these features; e.g., not only does a particular brand of shortening have many attractive features for frying chicken, no competing brands have these qualities.

7. The Halo Implication

- A true claim of product superiority in one way causes consumers to see superiority claimed in one or more additional ways. (Note: This implication has been particularly rife in advertisements for headache remedies, where true claims about the amount of pain-relieving ingredients in pills have led to the groundless implication that they are more effective than competitors in relieving pain.)

8. The Confusing Resemblance Implication

- Use of a specific word or phrase in a product claim that is similar to a more familiar, understandable word or phrase falsely implies the lattes: i.e., reference to a "cashmora" sweater implies the sweater is cashmere or labeling the product "aspercream" implies that it contains aspirin.

9. The Ordinary Meaning Implication

- Words or phrases with ordinary meanings are used in product claims and are mistakenly interpreted as implying their ordinary meaning; e.g., a breakfast juice's claim of more "food energy" does not imply more nutrients (ordinary meaning), but instead means nothing other than calories.

10. The Contrast Implication

- A product is contrasted to a competitor to show truthfully a certain difference, the implication being that additional contrasts are valid.

11. The Endorsement Implication

- Advertising messages center on celebrities or ordinary consumers trumpeting their satisfaction with the product, the implication being that consumers generally will experience the same satisfaction.

12. The Expertise Implication

- Product endorsers' advertise expertise, conceded to be true, is falsely implied to be relevant to the accompanying claims; i.e., a racing driver's expertise does not extend to judging the relative merits of toy automobiles.

13. The Significance Implication

- A message states a true but insignificant fact with the accompanying unjustified implication that the fact should matter to the consumer; e.g., while it may be true that a cigarette is low in tars and nicotine than competing brands, the difference may be so small as to have no significant effect on health risks.

14. Product-Specific Implication

- Numerous implications that foster unjustified beliefs about a particular type of product's advantage; e.g., medicines may truthfully claim that they relieve symptoms while falsely implying they cure the disease or condition.

15. The Puffery Implication

- Messages contain non-factual opinion statements praising the product, but they imply that the claim is nothing but subjective opinion and thus no objective factual basis for the claim exists nor is one intended to be conveyed.

Deceptive Communication in Personal Relationships

Most of us are partly political and economic animals, but I believe discussing this category "Personal Relationships" of deceptive communication will provide the most value to members of the Product Management team. I don't have the time or space to address everything I want to, so I'm going to leave you with this study.

Co-habiting couples in a student housing area at Michigan State University were asked to complete independently identical questionnaires dealing with numerous aspects of the role of deceptive communication in close relationships. When asked to estimate how much deceptive communication occurs in close relationships in general, the predominate response was a modest amount. When asked how much deceptive communication occurred in their own relationship, however, almost all respondents replied hardly any. Interestingly, they also reported that while their partners practiced little or no deceit, they were confident that they could detect such communication behavior should it rear its deceptive head.

It should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. LIVESTRONG is a registered trademark of the LIVESTRONG Foundation.